The long-term welfare impacts of natural disasters: Evidence from Ugandan landslides

When natural disasters displace households, impacts on welfare can last for years after the event and vary depending on the extent of response.

Between 2008 and 2018, around 265 million people were displaced by natural disasters around the world. While climate change threatens to increase the frequency and severity of natural disasters, studying the impacts of displacement is very difficult for two main reasons. First, natural disasters don’t strike randomly (some areas are more prone to disasters than other because of their geography among other factors), and people who are better off tend to avoid living in high-risk areas. Second, the very nature of displacement makes it difficult to collect data on all the people who were affected.

Earlier in 2022, an IGC study launched a survey to understand the long-run impacts of landslides on the households they displace. We worked in Eastern Uganda, a region that has experienced a series of devastating landslides over the last decade, displacing about 65,000 people. While the overall risk of landslides in the area is well-known, we show that the exact path of the slide is quite random. For this, we borrow a risk model from the geomorphology literature to adjust for any potential non-randomness.

Studying displacement

One of the hardest parts of studying displacement is knowing who was affected by the disaster and where they live now. We received invaluable assistance from contacts with considerable insight into the local conditions and landslide events through their work for the Uganda Red Cross Society. They compiled lists of all households living in affected areas at the time of each landslide. With extensive tracking and the assistance of local leaders, we were able to survey 91% of all households who were living in the study region at the time of the landslide, giving us a rare look into the long-run experiences of those who were affected.

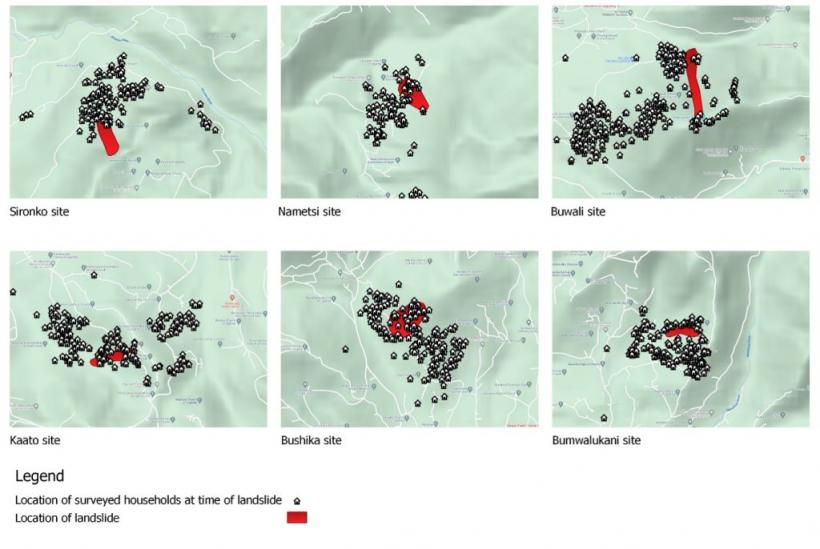

Figure 1: Map of landslide sites and household locations

Note: The maps illustrate the location of households at the time of the landslides as well as the exact landslide path.

What happened to households hit by the landslides?

The landslides were devastating, leading to substantial death and destruction of homes and land. Of the households in landslides’ path 39% were destroyed, and 27% experienced the death of a household member.Almost all households experienced serious damage to land, livestock, and property. The average repair costs (excluding what was financed by aid) were US$ 485 per household, representing more than nine months’ worth of total household income.

Two-thirds of affected households were forcibly displaced, though many eventually returned to their home villages. Nearly every displaced household moved to another village in Eastern Uganda. Among the displaced, about 40% remained outside their home village by the time of the survey.

Although almost no households relocated to urban areas, many sent migrants to cities. Urban migration after the landslide increased by 40%, and most migrants were still in cities at the time of the survey. New migration is pronounced among households with weaker urban networks at the time of the landslide, suggesting that households use both existing urban networks and new urban migration to cope with the impact of the landslide and view them as substitute strategies.

At the time of the survey, two to twelve years after the landslides, affected households are substantially worse off in several welfare measures, including mental health, housing amenities, and income.

Conflicting evidence on long-run economic impacts of natural disasters

Other studies of natural disasters, especially in wealthier countries, have documented neutral or even positive long-run economic impacts. Even in low-income settings, studies of earthquakes and the tsunami in Indonesia have found positive long-run impacts of natural disasters. We think our divergent findings can be explained by two key features of the post-disaster experience, displacement and aid.

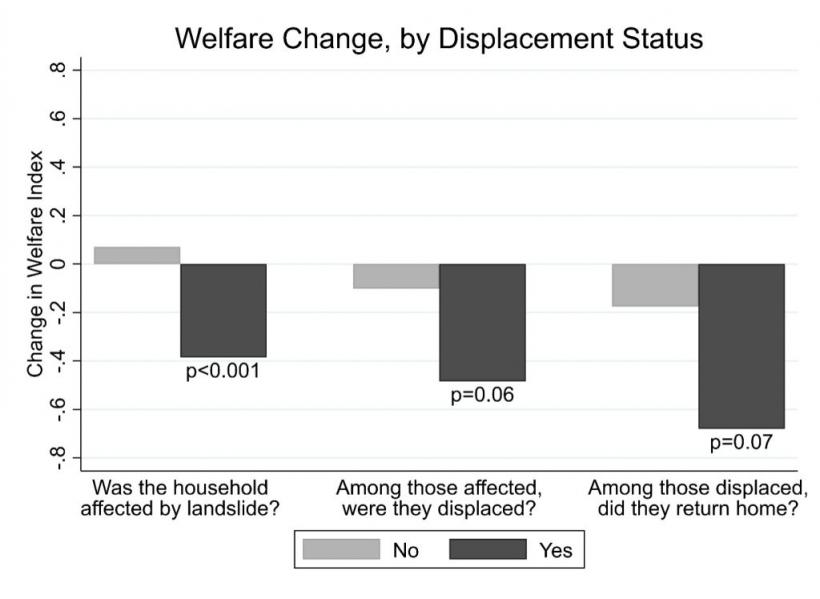

Not all natural disasters produce displacement, and those that do are especially hard to study. In our setting, we see that displacement plays a crucial role in explaining welfare impacts. Among those affected by landslides, displaced households experience a significantly bigger drop in welfare compared to households that remained in their home village. Among those displaced, the drop in welfare is most pronounced among households that moved again to return to their home village.

Figure 2: Displaced households experienced greater declines in welfare

Note: All households affected by the landslides experienced a decline in their welfare, while households that returned to their home village after displacement experienced the largest welfare decline.

Returning home after displacement and the impact of aid

Only about one-third of returnees give a reason for returning that reflects a voluntary choice, such as to reclaim land, because they did not like life in the relocation site, or because others were also moving back. The rest move back because they can no longer afford to live in the relocation site, or only had temporary arrangements.

Disaster aid also appears to help households cope with the impacts of landslides. In our data, households whose damages were mostly covered by aid experienced mitigated welfare impacts. This was, however, unfortunately rare as households in the landslide’s path received only about US$ 33, or 10% of the median cost of repairs. This may explain why the long-run economic impacts of natural disasters in settings with substantial disaster aid flows appear so different – as was the case following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami . Our findings thus underline the importance of reconstructive aid beyond the immediate relief which local actors could provide in Eastern Uganda.

Risk-mitigation strategies and further research

The substantial negative welfare impacts lend greater urgency to campaigns raising awareness of the risks, and to encouraging pre-emptive evacuations after heavy rains. According to our contacts from the Uganda Red Cross Society, the local population is often reluctant to engage in such risk-mitigating behaviour, despite the history of disasters. Our work also strengthens the case for pursuing permanent relocation to stable ground as a risk-reduction strategy. We believe that identifying programmes to encourage voluntary and sustainable pre-emptive resettlement is a promising avenue for future research.

Finally, the contrast of our findings to the more positive findings in the literature on disasters and displacement highlights the need for studies in a diverse range of settings. A focus on developed countries and well-known disasters, which receive widespread attention and generate substantial aid flows, can create a picture which is not representative of many other smaller events.