Rethinking VAT: Making sense of Zambia’s policy U-turn on VAT

On 28 September 2018, the Zambian Minister of Finance, Margaret Mwanakatwe, in her maiden budget address to Parliament, announced a major policy change set to turn the Zambian tax system on its head. Effective April 2019, Zambia will abolish Value Added Tax (VAT) and replace it with a non-refundable sales tax. This move re-opened a policy debate: Which consumption tax is more efficient – sales tax or VAT? This blog seeks to make the case for why VAT is still a better option than sales tax and analyses what seems to be the key instigator for the policy change- the large VAT refunds paid out to exporters.

VAT: A Cinderella story?

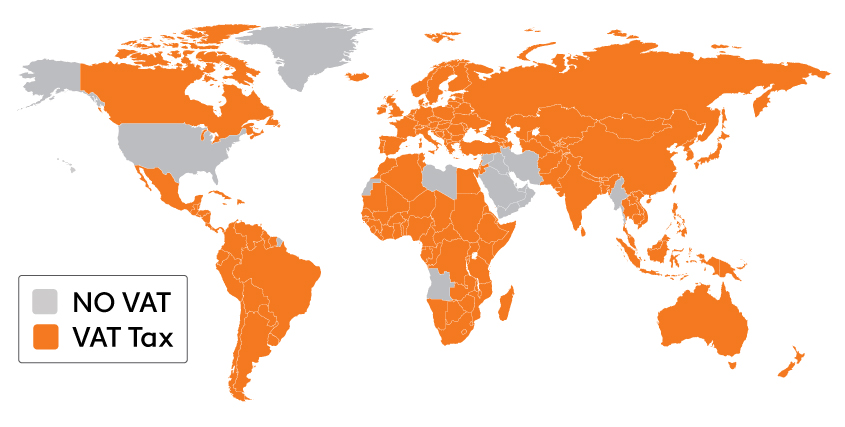

VAT has become the workhorse of the majority of developing countries’ revenue mobilisation strategies. A quick glance at a world map reveals that over 160 countries have adopted VAT, including more than 80% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Keen, 2016).

Source: Applicacious, 2016.

Source: Applicacious, 2016.

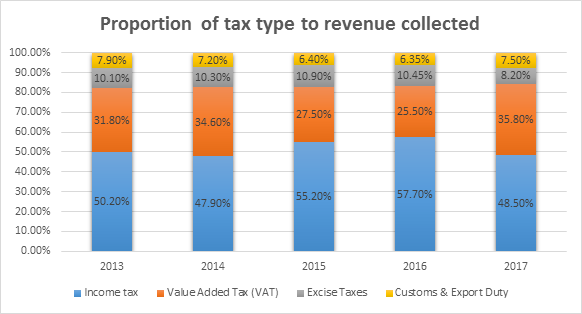

In many developing countries, VAT is the single largest contributor to the treasury, responsible for a quarter of all revenue mobilised (Gerard and Naritomi, 2018). In 2017, VAT contributed 35% of total revenue to the Zambian treasury (ZRA, 2018).

VAT versus sales tax: Incentives and enforcement

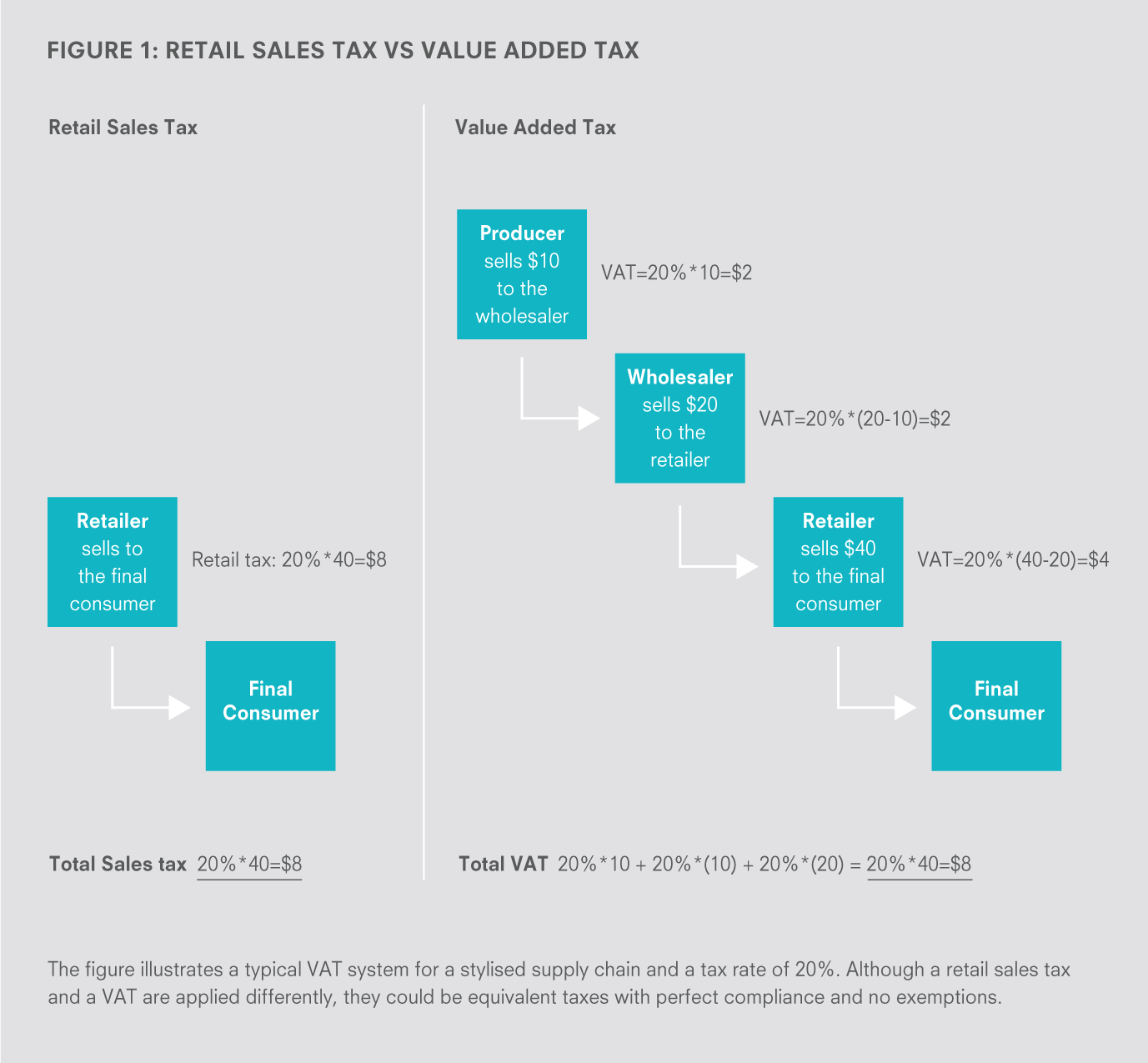

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between VAT and sales tax. Under a VAT system, the tax is collected on the value added at each stage while with sales tax it is collected at the final sales point. In a perfect world, with perfect compliance, no price cascading and no exemptions, the revenue collected from both systems should be equal. This IGC brief gives a thorough treatment of the difference between the two taxes.

The fundamental advantage that VAT possesses over sales tax is the self-enforcing mechanism it has in business-to-business (B2B) transactions (Gerard and Naritomi, 2018):

- With VAT, a business purchasing goods needs an invoice issued by a seller to deduct the VAT incurred on the transaction. The business selling the goods would prefer not to issue the invoice and under-declares its sales to the tax authority. This difference in incentives gives rise to the self-enforcing mechanism since the buyer will demand the invoice to ensure he/she receives the deduction.

- With sales tax, the buyer has no need to demand an invoice and it is up to the seller to declare the sale to the tax authority. This mechanism further creates an effective paper trail, which makes it easier for the tax authority to enforce compliance. Pomeranz (2015) provides excellent empirical evidence for the effectiveness of the self-enforcing mechanism for Chile and Wassem (2017) does the same for Pakistan.

If VAT is clearly superior to sales tax, why then is Zambia switching back to sales tax? The answer lies in the exemptions that often accompany VAT systems.

The exception to the rule: Tax exemption for exports

In most VAT systems around the world, many governments tinker with the VAT to achieve different policy objectives. Most countries, for instance, exempt basic goods consumed by the poor, such as bread, from attracting VAT. It is usually from these exemptions that unintended consequences affecting supply chains and revenue mobilisation tend to emerge (Gerard and Naritomi, 2018). In the Zambia case, it all boils down to the provision that goods and services destined for export, such as copper, incur VAT at a rate of 0% (ZRA, 2015). This means exporters are refunded the VAT they incur along the input value chain without having to remit any VAT on their final product sale. The practice of zero rating exports for VAT purposes is widely practiced in the majority of countries (Charlet and Owens, 2010). For economies and sectors within economies that are export oriented the question of how to manage exports for VAT purposes has always been contentious (Conrad, 2012). An IMF survey of 36 countries finds that refund payments have created tension between tax authorities and the business sector causing it to become the “Achilles heel” of the VAT system (Harrison & Krelove, 2005). In effect, the copper sector in Zambia is refunded the VAT it pays on its inputs.

The refund conundrum for Zambia

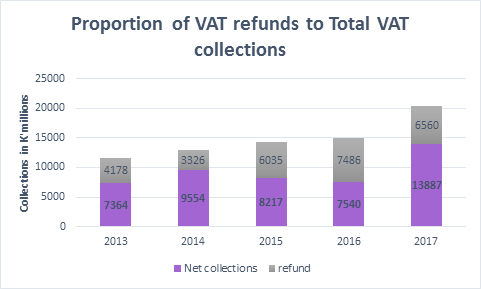

- In Zambia, refund payments have increasingly preoccupied the minds of policy makers in government. Figure 2 shows the proportion of refunds to total VAT collections in Zambia over the past five years (ZRA, 2018). Over the period, the net contribution of VAT has far surpassed the amount paid out in refunds however, the proportion of refunds to total VAT collections has been rising, almost doubling in 2015 from the previous year.

- Previously, the government’s strategy for dealing with refunds was to delay payment using them as a cheap source of short-term financing. The practice was so recurrent that the IMF, when calculating Zambia’s fiscal deficit, factors in delayed payment of VAT refunds, which was equivalent to 2.8% of GDP in 2017 (IMF, 2017).

- The Zambian government has in the 2019 budget buckled under the weight of paying out these refunds (Mwape, 2018). Faced with the legal obligation to pay them out, the Zambian government appears to have concluded that the payment of VAT refunds is a major revenue leakage and decided to do away with them completely by abolishing the entire VAT system.

The measure appears drastic when you consider that the performance of VAT in Zambia has been relatively good contributing the second largest share of revenue to the treasury over the last five years. See figure 3 (ZRA 2018). Given the buoyance of VAT what motivated such a drastic response to the refund problem?

Figure 3 Source: ZRA 2017 annual report

Figure 3 Source: ZRA 2017 annual report

The motivation for the policy change seems to emanate more from an urgent need for revenue. The country is currently experiencing rising fiscal demand from mounting debt obligations, an ambitious infrastructure development drive and pressure from social spending which is putting a strain on the public purse. This coupled with a strong sense that the mining sector, the biggest exporter and hence the primary recipient of the VAT refunds, is not paying its fair share of taxes. Government in the hunt for quick revenue gains has identified the elimination of VAT refunds as a quick win. The IMF observes that in countries where budgets are under pressure, forecasting and monitoring of refund payments is weak and collection targets are not being met, the payment of refunds tends to emerge as a major problem (Harrison & Krelove, 2005).

Implications and recommendations

Unfortunately, instead of plugging the leak, this decision might burst the dam. With the removal of the self-enforcing mechanism that makes VAT so effective, tax evasion is likely to increase across all sectors, leading to greater declines in revenue. Cost of production is also likely to rise as firms further down in the supply chain factor in the cost of the sales tax into their prices. One major exporter has estimated that the cost of production is likely to go up by at least 20 percent (Lusaka Times, 2018). For the domestic consumer prices are also likely to rise leading to a higher cost of living for the ordinary Zambian.

A better policy response would be to reform the VAT refund system rather than replace the entire VAT system with a non-refundable sales tax.

Possible reforms include:

- The use of special arrangements for exporters such as exempting capital imports that often lead to large refund claims from the VAT system. Zambia already uses a VAT deferment scheme that can be further augmented.

- Apply a zero rate on supplies to exporters reducing the possibility of claims. Some EU countries such as France and Ireland apply such measures.

Finally, the Zambian government needs to reign in excessive expenditure to minimise pressure on the revenue side of the budget.

References

Applicacious (2016). VAT-TAX Countries Map. Accessible: http://applicacious.com/what-you-should-know-about-vat-and-selling-internationally/vat-tax-countries-map/

Charlet, A. and Owens, J. (2010). An international perspective on VAT, reprinted from Tax notes in’tl, OECD, p 943. Accessible: https://www.oecd.org/ctp/consumption/46073502.pdf

Conrad, R. (2012) Zambia’s Mineral Fiscal Regime. London: International Growth Centre. Working Paper 12/0653

Gerard, F. and Naritomi, J. (2018). Value Added Tax in developing countries: Lessons from recent research, IGC Growth Brief Series 015, London: International Growth Centre. Accessible: https://www.theigc.org/publication/value-added-tax-developing-countries-lessons-recent-research/

International Monetary Fund/IMF (2017). Zambia Debt Sustainability Analysis: Country Report No. 17/327, Washington: International Monetary Fund. Accessible: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/pdf/2017/dsacr17327.pdf

Keen, M. (2016). Taxation and Development—Again, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, Fiscal Affairs Department.

Harrison and Krelove (2005) VAT refunds: A review of Country Experience. IMF working paper series WP/05/218

Lusaka Times (2018). “First Quantum Minerals warns that it will cut production at Sentinel once Sales Tax kicks in”. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2018/12/19/first-quantum-minerals-warns-that-it-will-cut-production-at-sentinel-once-sales-tax-kicks-in/

Mwape, N. (2018). K9.6bn lost yearly in VAT refunds, Zambia Daily Mail Limited. Accessible: http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/k9-6bn-lost-yearly-in-vat-refunds/

Pomeranz, D. (2015). “No Taxation without Information: Deterrence and Self-Enforcement in the Value Added Tax”, American Economic Review, 105(8): 2539–69.

Waseem, M. (2017). Information, Asymmetric Incentives, Or Withholding? Understanding the Self-Enforcement of Value-Added Tax? Oxford Centre for Business Taxation working paper series WP18/08

Zambia Revenue Authority/ZRA (2017). VAT Guide. Accessible: https://www.zra.org.zm/download.htm?URL_TO_DOWNLOAD=//web_upload//PUB//VAT%20Guide%20201710082017164346.pdf

,https://www.zra.org.zm/download.htm?...//VAT%20Guide%20201710082017164346

Zambia Revenue Authority (2018) ZRA Annual Report 2017 ttps://www.zra.org.zm/manageUpload.htm?ACTION_TYPE=view&CIRCULAR_KEY=2017%20ANNUAL%20REPORT&DOC_ID=999000000005561