The conundrum around India’s new agricultural reforms: Where do farmers stand?

While the recent agricultural reforms in India have been hailed by some experts as a much-needed move towards privatisation and liberalisation of the sector, there is also a concern amongst some that the opening up of the agricultural market may also lead to corporate cartelisation. Additionally, critics have pointed out the procedural inadequacy of the reforms and how many key stakeholders were not consulted, as well as the regulatory architecture and its ambiguity making accountability a cause for worry. Strengthening farmer producer organisations, providing better infrastructure, and institutional support, amongst others, should be key areas for reform going forward.

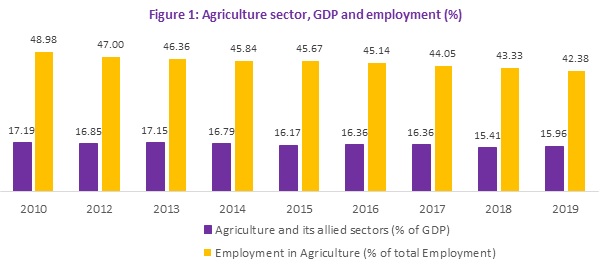

The pandemic this year has resulted in a wave of disruptions to people’s lives and livelihoods. In particular, it has created further challenges for Indian farmers as the Government of India announced three new agriculture reforms bills during the pandemic, because of which Indian agriculture has been in the national spotlight amidst the crisis. Agriculture and its allied sectors are livelihood sources for around 54.6% of the population, contributing around 16.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Economic Survey 2019-20). Though India’s agricultural markets have diversified across public and private institutions, and have grown in size and complexity, employment in agriculture has witnessed a declining trend, as has agriculture’s contribution to India’s GDP (Figure 1). The volatility of agricultural markets is deeply contested in the economic and public policies across the central and state governments.

Arguments for and against agricultural reform

The recent announcements of agricultural reforms were about:

(i) Bypassing the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMCs) Act to open up the market and include private players, create alternative trading channels, remove interstate trade barriers, and promote e-trading

(ii) Setting a legal framework for contract farming

(iii) Revisions to the Essential Commodities Act

The proponents for these reforms state this as the liberalisation of the agriculture sector (or the 1991 moment in agriculture) which will bring more private players and investment into this sector and therefore, give more freedom of choice to farmers to sell their produce. On the other hand, there is a concern that the opening up of the agricultural market may also lead to corporate cartelisation and may see placement effects as business tend to be selective towards its operating geographical area, often choosing areas with better infrastructure, availability of skilled farmers and fewer competitions. Additionally, experts have also raised concerns to the manner in which the bills were passed in the parliament, citing non-consultative approachesand inadequate discussions with stakeholders (i.e. standing committee, state governments, farmers, traders, and policy experts). By doing that, the Government of India demonstrated its willingness to use the COVID-19 crisis and the ordinance route to unilaterally push through reforms, without having any stakeholder’s involvement. Furthermore, there is an apprehension on the regulatory architecture and role of state and central governments when it comes to decision-making in the agriculture sector and raises concerns on accountability measures.

The current government’s agenda for doubling farmers’ income has been much discussed to manage agrarian distress. The minimum support price (MSP) as a legal right is the current contention amongst farmers and government. MSP acts as a mechanism to protect farmers from distress sale of farm goods and enable them to fetch the right price for their produce. In 2012-13, only 6% of total farmers in the country had gained from selling wheat and paddy directly to any procurement agency.And even before the recent reform announcements, 19 states had already allowed direct purchases from processors and bulk buyers; it is also further stated that in 2012-13, only 25% of transactions had been conducted in APMC mandis of all produce and 55.9% were sold to private traders. Thus, farmers have been trading outside the APMCs and which bears an impact on their income.

An analysis of farmer incomes between the years 2003 and 2013, suggests that at an all-India level, there is no doubling of farmer income, except for states like Odisha, and of particular concern are states of Bihar and West Bengal where average monthly income had declined over the period. Similarly, other analysis of farm incomes in India from 1983–84 to 2011–12 show that the growth in farmers’ income that was seen post-2004-05, which helped to promote inclusive growth and reduce income disparities, could not be sustained beyond 2011-12. Furthermore, an analysis of 10 crops sold in October 2020 shows that in 68% of the instances, farmers sold crops below the MSP in mandis; another analysis cited that at least INR 1,881 crore were denied to farmers on the aggregate by having to sell their produce below the MSP in October and November 2020.

On the other hand, there is an argument that the notion of having MSP as a legal right may not fulfill the objective of protecting farmer incomes, as per Hussain, Ramaswami and Singh, for cases such as Food Corporation of India (FCI) does not procure in the required quantity or post reform, may trade in the new market to cut down the cost by avoid paying mandi fees and taxes. If that happens, it will have significant fiscal consequences for states. Additionally, there are concerns in terms of increasing farmers’ income solely via farm produce, particularly income coming from cultivation and livestock which dropped significantly from 60% of average farm income from 2012-13 to 43% in 2015–16. Thereby, income diversification across both farm and non-farm activities have been suggested as a way forward to increase the income levels for the rural economy.

Contract farming and farmer producer organisations

Regarding India’s contract farming bill, the strong presence of notional contracts amongst farmers and firms raises an apprehension towards the enforcement of written contracts and the process of grievance/ dispute redressal mechanisms. Additionally, small and marginal farmers, who constitute around 86.07% of Indian agriculture with less than two hectares of landholding, have mostly been excluded from being part of this contract farming structure due to weak bargaining power, the enforcement of contracts, high transaction costs, and quality standards. Apart from these, smallholder farmer's participation in agro-industrial development might not be addressed adequately in the contract farming model and the concerns may remain around diversification of produce. However, as a proposed solution it has been argued that to strengthen the small and marginal farmer's bargaining power and market-access, farmer producer organisations (FPOs) should play a critical role and become necessary in Indian agriculture. Even though in the union budget of 2019-20, the government had announced the formation of 10,000 new FPOs, it is important to factor in the time and additional training and capacity building that FPOs require to structure and function successfully, which is about three to five years.

Moreover, while India is said to have achieved sufficiency in food production, it is also the home to 189.2 million undernourished people. As per the Global Nutrition Report (2020), India is not on track to meet any of the ten 2025 global nutrition targets. Furthermore, the Global Hunger Index (2020) ranks India at 94 out of 107 countries. Evidence suggests that the average daily calorie consumption in India is below the recommended diet for all groups, except the richest 5% of the population. Other evidence also states that 63–76% of the rural poor could not afford a recommended diet in 2011.There is a growing concern in terms of food security and nutrition amongst rural households, and without having the necessary income support for farmers, these policy changes may influence the decision of farm production (protein-rich vs. carbohydrate-rich).

Reform priorities

In terms of the way forward for Indian agricultural reform, some key points for consideration are:

- Agriculture is a state subject and having a centralised policy requires the participation of all the stakeholders along with a farmer-centric approach.

- The opening of the agricultural market requires better institutional and infrastructure support in place for farmers.

- In terms of addressing the grievance/redressal mechanism, the 2003 model APMC Act was a better system in terms of addressing this, and it also had the counterparty risk assurance.

- There is a need to improve farmers’ income and shift the focus from production to farmers’ livelihoods.

- Policies to meet the basic requirement of water, improvements in land, and access to technology are essential

- Providing institutional support such as rural business hubs and strengthening of FPOs for small and marginal farmers to actualise the right price is essential.

- With adverse climate change impacts, reforms are needed to help farmers to mitigate the risks of weather and price volatility.

To conclude, it is important to understand whose needs are we putting first, consumers or producers (farmers), and to aim to achieve the balance while reflecting on “Whose reality counts? and Whose priorities?”.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.