The structural constraints limiting Zambia’s economic response to COVID-19

Health pandemics, like other calamities, are great revealers. Not only do they come at a colossal cost to human life, but often expose and lay bare the structural problems riddling an economy. The COVID-19 pandemic is emblematic of this. It has affected 184 countries around the world with preliminary estimates indicating that it will cost the global economy at least USD 1 trillion in 2020 alone. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already warned that the economic fallout will be worse than the great financial recession of 2008. The IMF has projected that the Zambian economy will experience negative growth this year, shrinking by at least 2.6% (Ng'andu 2020). The last time Zambia registered negative GDP growth was over 20 years ago (IMF 2004). The Zambian government is also forecasting a revenue shortfall of 19.7% in 2020 (Ng’andu, 2020). The most harrowing cost will, of course, be the loss of human life.

Infections have only just begun to accelerate on the African continent. Zambia, as of 21st April 2020, has recorded 70 confirmed cases and 3 deaths. What makes this pandemic particularly difficult for countries like Zambia are the structural constraints that already exist in their economies. This blog explores four of these constraints, and how they are limiting the Zambian government’s response to COVID-19 as well as what can be done to relax them.

1. Public debt: Caught on the back foot

One of Zambia’s biggest structural problems is a heavy reliance on unsustainable debt. From 2010 to 2018, Zambia’s debt increased from a debt-to-GDP ratio of 20% to 78% of GDP (IMF 2019). Even before the COVID-19 crisis, the country was teetering on the brink. The signs of debt distress were already beginning to show with the burden of servicing debt payments exerting pressure on the currency, which from March 2019 to March 2020, lost 24% of its value against the dollar in nominal terms. In the month following the onset of the pandemic, the currency lost another 26% (author’s calculations). The onset of the coronavirus, therefore, caught Zambia on the back foot. Not only has the high debt burden limited the options available to the country to respond to the health crisis, but has also put Zambia at an even higher risk of debt default.

However, there are still options on the table:

- Zambia has already started restructuring its debt. Negotiations to defer debt payments are an important option. The China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) estimates that Chinese loans account for about 44% of Zambia’s debt, so the negotiating of Chinese infrastructure loans will be particularly important.

- The other is to try to access emergency funds that have been made available to poor countries through multilaterals such as the World Bank and the IMF. The long-term solution, though, should be to limit debt contraction and borrow on a sustainable level so as to withstand unexpected crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Poverty and inequality: The bane of limited social protection programmes

One in every two Zambians lives below the poverty line, with a substantial percentage living just above it and at risk of slipping into poverty (IMF 2019). Even amidst a period of high economic growth, poverty in Zambia remained high and inequality worsened, revealing a deeply structural problem. Given the policy responses needed to quell the spread of COVID-19 – lockdowns and restrictions on movement –, the pandemic will undoubtedly worsen conditions for the poor.

Social cash transfer schemes have proven to be the most effective tool for poverty alleviation for countries such as Zambia. Of the eight million Zambians living in poverty, only 700,000 are on a social cash transfer programme. Currently, Zambia runs other programmes which have been found to be less effective such as the Farmer Input Support Programme, which in 2020 was allocated 5% of the budget. During periods of disaster, it is often the most vulnerable that are hardest hit and find it the most difficult to recover. What the COIVD-19 pandemic has exposed is the inadequacies of current social protection programmes and the urgent need to restructure them. Having a social protection programme that is effective, is vital, precisely because of unexpected calamities such as COVID-19.

In the short term, donors who were responsible for financing the initial round of social cash transfers could potentially step in to assist. They have the advantage of already having systems in place. There has also been a call for them to redirect other non-essential funding (to other programmes) to the COVID-19 response. It would be good to focus on such an area. However, in the long run, social protection programmes need to be restructured so that they work for the most vulnerable Zambians.

3. A large informal sector: Caught in the middle

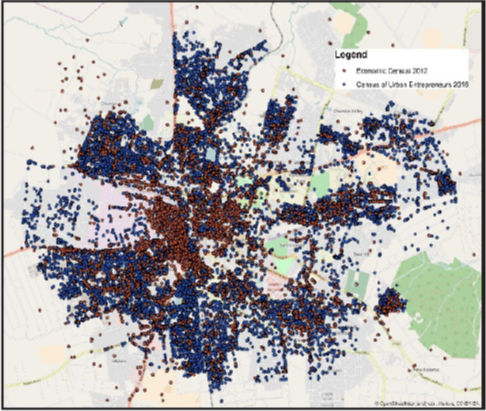

In Zambia, 90% of the workforce is estimated to work in the informal sector, with the majority in subsistence agriculture (Shah 2012). An IGC census of firms in Lusaka – Zambia’s capital – found that 52% of Lusaka’s 47,428 firms are informal. This is only counting businesses with a fixed location and excluding traders who operate from make-shift stalls or no stalls at all. Yet, informality is one of the biggest challenges that compounds the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. For the majority (90%) of Zambians working in the informal sector, most of their income is earned on a daily basis. This makes stay-at-home orders and lockdowns difficult to comply with. The IGC firm census further reports that these businesses largely fall into the categories of retailing, the accommodation and food industries, as well as other services (the vast majority are hairdressers): all client-facing enterprises.

Source: The Urban census of Lusaka Enterprises (2016)

What is even more concerning vis-à-vis the spread of COVID-19, is the high level of firm clustering in the city. The map above shows the agglomeration of firms in Lusaka. While Zambia hasn’t gone into a full lockdown, the high level of clustering means stay-at-home orders will be particularly important in containing the spread of the disease. However, these containment measures will mean many individuals’ livelihoods will be threatened. The Zambian government is yet to announce any specific measures targeted at informal sector workers. The tax measures that have been announced are targeted at VAT-registered suppliers and exporters who tend to be larger and more formal firms. Because in Zambia poverty is concentrated in rural areas, this group will most likely also not benefit from social cash transfer schemes should they be ramped up. Which means informal sector workers will likely fall through the cracks. Specific measures, therefore, need to be taken to target this group. Offering of food relief in urban centres is one potential option that would limit the need for informal traders to continue operating during this period.

4. Continued reliance on a single commodity prone to global shocks

In many ways, Zambia remains a mono-economy still heavily reliant on copper mining. The mining sector is responsible for 70% of exports, accounts for 70% of foreign currency earnings and 26% of the treasury’s revenues (Liebenthal and Cheelo 2018). It also provides some of the best paying jobs that support Zambia’s emerging middle class. The COVID-19 pandemic has hit commodity prices for base metals like copper. The price of copper has already fallen by 9.6% over the past two months. This continued dependency on the base metal will exacerbate the crisis in multiple ways. The reduction in payment of taxes will reduce the revenue available to the government to respond to the crisis. The revenue shortfall also risks widening the budget deficit with revenues falling far below the projections in the budget. As a primary source of foreign exchange, the slump in prices has also contributed to the sharp depreciation of the Kwacha. This is, in turn, making it more expensive for the Zambian government to meet its debt obligations.

The mining sector, through the influential mining lobby (the Zambia Chamber of Mines), has already requested for a stimulus package to help cushion the effects of the crisis. But given the multiple challenges the government is facing, there will be more important items on the Zambian government’s list of priorities. In the short term, the sector will be one of the primary beneficiaries of the measures the Zambian government has taken to free up liquidity, including the dismantling of arears owed to the private sector. In the long term, this crisis emphasizes the importance of diversification from dependency on copper, a stated but often elusive policy goal. Diversification will ensure a multiplicity of sources of foreign currency and revenue. COVID-19 will affect all sections of the economy, but the crisis has accentuated why it is important to take the diversification agenda from paper to practice.

Conclusion

It is important to end by recognising that the COVID-19 pandemic is first and foremost a health crisis. The focus of the Zambian government is and should continue to be on limiting the effects of the public health crisis, especially the loss of life. The great hope following the COVID-19 pandemic is that Zambia will not default back to the status quo once it is over but will work on relaxing these structural constraints. This will enable the country to better withstand future crisis and deal with them effectively.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.

References

Ashraf, N, C Chiu, A Delfino, E Glaeser and N Swanson (2017), “Urban density, trust, and knowledge sharing in Lusaka, Zambia”, International Growth Centre. Policy brief 41409 . https://www.theigc.org/publication/urban-density-trust-knowledge-sharing-lusaka-zambia/

Bhorat, H, N Kachingwe, M Oosthuizen and D Yu (2017), “Growth and income inequality in Zambia”, International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Policy-brief-Inequality.pdf

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (2020), “Zambia Overview”. https://eiti.org/zambia

International Monetary Fund (2004), “Zambia: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix”, Country Report No. 04/160, Washington: International Monetary Fund. Accessible: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2004/cr04160.pdf

International Monetary Fund (2019), “ZAMBIA 2019 Article IV Consultation—Press Release”, Staff Report: Country Report No. 19/263, Washington: International Monetary Fund. Accessible: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/CR/2019/1ZMBEA2019002.ashx

Mfula, C (2019, January 3), “Zambia says mines have failed to show impact of higher taxes”, Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zambia-mining/zambia-says-mines-have-failed-to-show-impact-of-higher-taxes-idUSKCN1OX0JH

Minec (2020, February 17), “The impact of COVID-19 on Metals and Crude Oil prices”, Mintec Website. https://www.mintecglobal.com/top-stories/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-metals-and-crude-oil-prices

Ng'andu, B (2020), “Statement by the hon. Minister of finance on the impact of the coronavirus (covid-19) on the Zambian Economy”. https://www.zambiahc.org.uk/news_events/statement-by-the-hon-minister-of-finance-on-covid-19/

Ng'andu, B (2020), “Statement by the hon. Minister of Finance on further measures aimed at mitigating the impact of the Coronavirus (Covid-19) on the Zambian economy”, Government of the Republic of Zambia, Lusaka.

Ng'andu, B (2019), 2020 budget address by Honourable Dr. Bwalya K.E. Ng’andu, MP, Minister of Finance. Delivered to the National Assembly on Friday 27th September, 2019. http://www.parliament.gov.zm/sites/default/files/images/publication_docs/2020BUDGET-SPEECH.pdf

Nkomesha, U (2020, April 1), “Some mines face closure amidst deteriorating copper prices, warns Chamber”, News Diggers. https://diggers.news/business/2020/04/01/some-mines-face-closure-amidst-deteriorating-copper-prices-warns-chamber/

Ofstad, A and E Tjønneland (2019), “Zambia’s looming debt crisis – is China to blame?”, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2019:01). Accessible: https://www.cmi.no/publications/6866-zambias-looming-debt-crisis-is-china-to-blame

Shah, M K (2012), “The informal sector in Zambia: can it disappear? Should it disappear?”, International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/publication/the-informal-sector-in-zambia-can-it-disappear-should-it-disappear-working-paper/

South China Morning Post (2020), “IMF warns coronavirus recession could be worse than 2008 financial crisis”, https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/3076513/imf-warns-coronavirus-recession-could-be-worse-2008

The John Hopkins University and Medicine Corona Virus Resource Center (2020) https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

The New Humanitarian (2015, April 9th), “Pros and cons of Sierra Leone's Ebola lockdowns”, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2015/04/09/pros-and-cons-sierra-leone-s-ebola-lockdowns

Trading Economics (2020) Zambian Kwacha2013-2020 Data https://tradingeconomics.com/zambia/currency

UNCTAD, “This is how much the coronavirus will cost the world's economy, according to the UN”. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/coronavirus-covid-19-cost-economy-2020-un-trade-economics-pandemic/