From Zika to COVID-19: Can we learn lessons across pandemics?

Evidence gathered during the course of the Zika outbreak in the Americas in 2015 provides important lessons for policymakers in today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought social life and economic activity to a near halt in most countries around the globe. Viruses and viral outbreaks have shaped the course of human history, with COVID-19 representing the latest round of the perpetual battle between mankind and new viruses. In each case, societies are forced to quickly put in place policies to mitigate the health impacts of a new virus.

Viral outbreaks certainly differ in many important ways, such as the individuals most at risk e.g. pregnant women for Zika and the elderly for COVID-19, their vectors of transmission, their fatality rate, and their degree of contagion or basic reproduction number. Despite these differences, policy responses used to tackle viral epidemics have tended to be similar across time and countries – social distancing, quarantines, school closures, and information campaigns are the policy instruments normally available.

The Zika epidemic presents the first ever known association between a flavivirus, carried by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, and congenital disease (a disease present at or before birth), representing a “new chapter in the history of medicine”. The congenital disease most closely linked to the Zika virus in the 2015 epidemic was microcephaly: a neurological disorder among newborns in which the occipitofrontal head circumference is smaller than 98% of all newborns.

Public health alerts during the Zika epidemic

In a recent working paper, we study how households and health sector personnel responded to public health alerts during the Zika epidemic in Brazil in late 2015, that quickly spread to become a pandemic by early 2016. The detailed timeline of the epidemic is as follows. In March 2015, the WHO received notification from the Brazilian government regarding an illness transmitted by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, but not detected by standard tests. Until early November 2015, it was therefore known that Zika was present in Brazil but the perception was that it was a “dengue-like” infection, and harmless to newborns. However, on 11 November 2015, the Brazilian government issued an alert emphasising an upsurge in microcephaly in the North East of the country, and establishing the link to Zika. Within a week, a WHO communique had made explicit mention of microcephaly and the potential link to Zika.

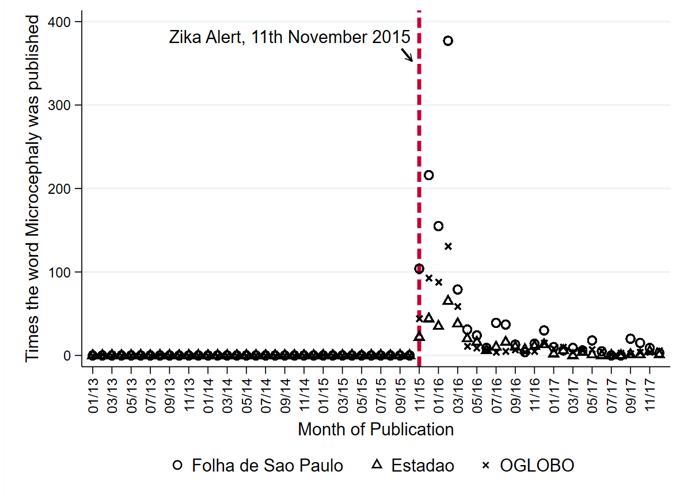

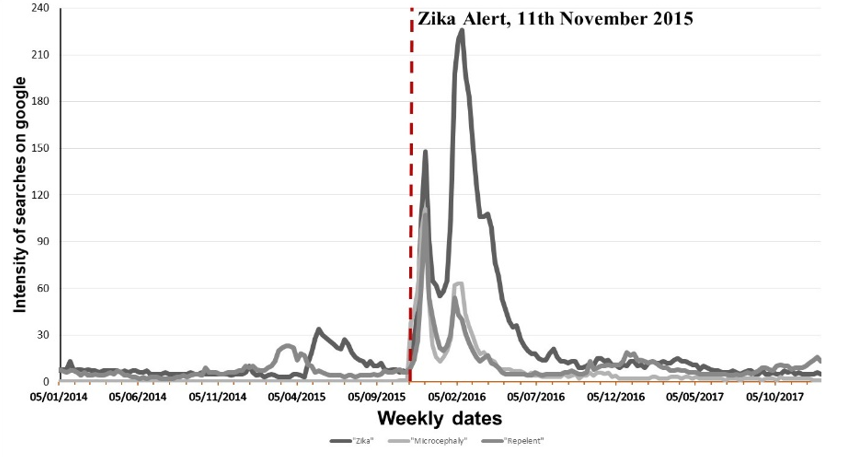

The public health alert was immediately broadcast on TV media. Figure 1 shows the number of times microcephaly was reported in three leading national newspapers in Brazil. Figure 2 shows the time series of Google searches for Zika, microcephaly (in Portuguese), or repellent.

Figure 1: Media mention of 'microcephaly' in three leading newspapers

Figure 2: Google searches for Zika, microcephaly, and repellent

In the context of Zika where transmission is mainly through mosquitos, the health alert was designed to influence the behaviour of those at-risk, namely pregnant mothers. Public health alerts related to COVID-19 instead aim to alter the behaviour of both those most at-risk (encouraging them to self-isolate) and those less at risk themselves, but whose behaviour can impose an externality on those at risk through human-to-human contagion. Using tens of millions of administrative records from vital statistics and hospitals, we study how households, in particular pregnant women, responded to this health alert in Brazil.

A significant fall in conception

Households in Brazil did indeed dramatically change behaviour after the public health alert. In particular, women were far less likely to become pregnant. We find a near 7% reduction in conception rates as a result of the public health information provided on Zika, corresponding to around 18,000 fewer children being conceived throughout Brazil in each month after the alert.

The response in rates was triggered almost immediately. Conception rates started to fall within a week of the health alert, and it took close to a year before they returned to pre-epidemic levels. In the current COVID-19 crisis, this suggests at-risk individuals can respond quickly to public health alerts. Moreover, it further suggests that the behavioural change can last much longer than the period of the epidemic itself, with a slow convergence back to pre-epidemic norms.

Households responded differently

Not all households in Brazil were equally responsive to the public health alert on Zika. The largest falls in conception rates occurred among older and higher socioeconomic status (SES) women. Does this mean that younger and lower SES women were not receiving the same information, or were not responsive to it?

To explore this further, we estimate the likelihood of a child being born with microcephaly among different groups of women. Pre-alert, we see differences in microcephaly risk, with higher SES mothers having lower risks. However, these risks equalise across all mothers, including between high and low SES mothers that conceived after the public health alert. This suggests that all pregnant women, irrespective of their age or SES, were able to take precautions during pregnancy to avoid mosquito bites and hence the risk of microcephaly. In other words, all women responded to information, but just in different ways.

In particular, the cost of delaying pregnancy might have been especially high for lower SES women. In the Brazilian context, this might be because of the difficulty of obtaining access to family planning facilities. However, the costs of avoiding mosquito bites during pregnancy are relatively low, and can be borne by all through simple preventative measures such as using repellents or wearing long-sleeved clothing.

In the COVID-19 crisis, this suggests that public health advice, for example, related to social distancing, might be less adhered to among those for whom such advice is the costliest to follow, for instance, because of the need to go out to work and earn. These groups might be helped through alternative policies that reduce such costs, such as targeted social assistance during the crisis that eases earnings losses. This should be done so quickly, given such households are likely to be liquidity-constrained and unable to bridge shortfalls between when earnings fall and assistance arrives. These groups might also be targeted through a combination of information and behavioural interventions that other studies have shown to induce short-run changes in health-related behaviours.

Trust in media matters

We find greater reductions in conception rates in response to the public health alert in Brazilian states with higher levels of trust in newspapers. Clearly, the messenger, and not just the message, matters in getting information across to the public. In an age in which the number of media sources of information have rapidly multiplied, and when some media outlets have their credibility questioned by politicians, this might be an important element of how households, in Brazil and elsewhere, respond to the current crisis.

Internal collaboration is crucial

Finally, our work in Brazil highlights how the ability to access and analyse real time administrative data can provide leading indicators that help spot viral outbreaks well before they become officially recognised. For example, vital statistics records from Brazil show that the incidence of microcephaly started to rise some months before the public health alert was issued in Brazil, or by the WHO. At least among countries with such administrative data infrastructure, new collaborative work between data scientists, epidemiologists, and social scientists is needed to use this real time data to combat emerging viral outbreaks.

Policy implications: Important lessons should be learned from the Zika outbreak

The threat of Zika has not diminished: the Aedes Aegypti mosquito infects around two million Brazilians each year, and 300 million globally. Work in life sciences to map global environmental sustainability for the Zika virus, suggests over two billion individuals currently inhabit areas with suitable environmental conditions. However, individuals are now much better informed of risks. No doubt over time the same will apply to COVID-19, but the lessons above remain valuable for whatever lies in store in future years. The ability to ensure individuals quickly change behaviour will continue to be one of the frontline policy responses available to governments in the face of a new viral threat.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IGC.