Improving women's political representation: Insights from Sierra Leone

Women’s political participation is especially limited in low-income countries like Sierra Leone. While provisions like quotas for women in elected office are useful to improve representation, deeper structural issues like systemic gender gaps, social norms, and barriers to upskilling must first be addressed to improve women’s political participation in the long run.

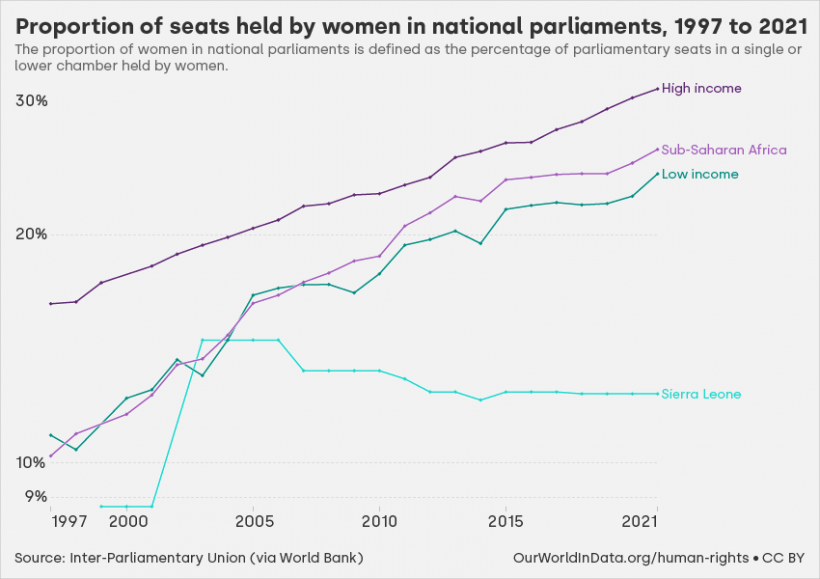

The limited participation of women in politics is even more pronounced in low-income countries. Only 27% of parliament seats on average are held by women. Even though women’s representation in the parliament has been rising, a persistent gap of 7 percentage point persists between high-income and low-income countries (Figure 1).

The gender gap in political representation is still pervasive at the ground level. For example, data from UN Women about local government positions reveals that in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) only 25.3% of local seats are held by women, relative to 36.3% in North America and Europe. These patterns suggest that the world–particularly LICs–face a clear lack of representation of women in political bodies.

Figure 1: Evolution of the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments

Notes: Overall global trend indicates an increasing participation of women in national parliaments, but lower income countries lag significantly behind. Source: Our World in Data, 2023.

Political representation of women in Sierra Leone

In Sierra Leone, the problem is even more pronounced relative to other LICs. During the last elections in 2018, women’s representation both in parliament and in local councils was substantially lower than the average for SSA, accounting for 12% of parliamentary seats and 17% of local council seats based on data from the National Electoral Commission of Sierra Leone (NEC). As shown in Figure 1, the underrepresentation of women in Sierra Leone not only lags behind high-income countries but is also stagnant relative to the progress other LICs have made in the last 20 years.

Limited participation in politics might be the consequence of deeper and more structural issues faced by women. Using NEC data, we find that political parties can be a bigger barrier to women’s political representation than voters. The share of women candidates is about 12% in parliamentary races and 18% in local council races. This share is almost identical to the share of women who end up winning seats. This implies that voters are not systematically voting out women candidates, rather the number of women who contest these races is limited to begin with. Thus, it seems that the process by which party symbols are awarded is very important in determining whether women end up in important political positions.

The UN Women data allows us to measure the proportion of women represented in local government relative to the whole population. This measure captures how scarce are women in politics among citizens rather than among political leaders. For local government, this is quite an important statistic as citizens are more likely to interact with political leaders at this level. In this domain, Sierra Leone also appears to be quite underrepresented, particularly for a country of its size. Across SSA, the average number of elected women per million inhabitants is 39.8 while Sierra Leone only has 11 elected women per million inhabitants. Countries like Ghana, Nigeria, and Malawi have even smaller women representation per capita, but they are also more populous than Sierra Leone.

To address this challenge, the Sierra Leone government passed the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Act which aims to assure 30% of appointed and elected positions, including parliament and local council seats, to women by allocating quotas.

Barriers to women's participation in politics

Regardless of whether a quota system is implemented to guarantee more women’s representation, there are two additional challenges:

- Systemic gender differences imply that the pool of women with the qualifications and experience to run for office might be substantially smaller than the pool of men.

- Political parties are still important gatekeepers of the political arena, and they are heavily run by men. Thus, the problem is not only finding qualified women to run but also getting political parties to embrace meaningful women’s representation and support women in the candidate selection processes.

Sierra Leone has one of the highest levels of gender inequality, ranking 181 out of 191 countries on the UN’s Gender Inequality Index. In terms of education, women are systematically disadvantaged. According to an analysis by UNESCO of the education sector in Sierra Leone, women are more likely to drop out of school than men. The report highlights that as of 2020, for every 100 boys completing senior secondary school, only 66 girls complete it. These differences in education affect the pipeline of men and women that consider running for office.

Scarcity does not mean that profiles of qualified women who can contest elected office do not exist. This is why studying the role political parties play when selecting candidates is crucial. Understanding these two barriers to women’s representation underpins our work in Sierra Leone.

Knowledge sharing with political parties can improve women’s representation

Our study aims to identify and screen qualified and popular new entrants into politics that can be potential candidates for local government in Sierra Leone and then share this information with political parties. With this intervention, we aim to close information gaps parties have about qualified and popular candidates, particularly by providing information on potential candidates parties might otherwise overlook.

We first conduct a series of structured private nomination processes in which we ask citizens to name both men and women in the community who would make good local councillors. This approach allows us to gauge the ease of finding women who can be potential candidates and interested and qualified to run for local office. Once we find these popular nominees, we screen them to understand their qualifications to run for local government. We then share this information with parties to help them in their candidate selection process. We study how parties react to our randomly seeded information, and how likely they are to pick candidates from our lists, particularly women.

As a part of our ongoing data-collection using around 3000 surveys, some key facts about the nomination process shed light on the constraints to women’s political representation in Sierra Leone:

- We find that citizens in general nominate very few women to run for local office. When unprompted to focus on gender, men nominate women less frequently than other women, but this difference is small. Only 27% of men nominate women, while 34% of women nominate other women. This result is important as it explains popularity differences by gender in our study.

- Even when prompted to think about women who stand out, we find that only 50% of respondents actually nominate a woman to run for local office. Thus, there might be important constraints to women’s representation coming from voters' knowledge and social norms about women in political leadership positions.

The differences between nominated women and men

The data we have so far also allows us to characterise how different the nominated women and men that come out of this process are:

|

|

Nominated men |

Nominated women |

|

Average years of schooling |

12 |

11 |

|

Has community leadership experience? |

80% |

70% |

|

Has experience working on local development projects? |

64% |

43% |

|

Is registered to a political party? |

68% |

52% |

|

Agree to have their profile shared with political parties to be considered an aspirant for Local Council? |

89% |

80% |

Note: When women do not agree to have their name shared, they often mention reasons associated to structural gender inequalities in our context, like a lack of interest in politics, the financial costs of running for office, and safety concerns.

Overall, our preliminary data already suggests there are many reasons for why women fail to be represented in local government. To begin with, even among popular women citizens who may aspire for local government, they are obstructed as they gather relevant skills for the local elected office through different life experiences. Simultaneously, social norms around women's involvement in politics might prevent them from becoming popular enough to run for office. Both these reasons imply that there are fewer women inside traditional pipelines that feed into politics. Women can have meaningful effect on governance and it is essential to support them.