Can public-private partnerships (PPPs) bridge the infrastructure gap in fast-growing cities?

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have become an increasingly popular policy option to procure vital urban infrastructure. They hold the potential to leverage private sector finances and expertise towards projects that are in the public interest. However, evidence on their success is mixed. Crucially, PPPs are not a solution to a borrowing problem and cannot replace the need to build public capacity in project management and planning.

Low-income countries need significant investment to build infrastructure and provide critical services for growing populations. Africa alone needs US$ 100 billion every year to meet its infrastructure needs. Much of this investment will need to take place in cities to provide transport, water supply, and sanitation investments that can enable prosperity as rapid urban settlement takes place. But who should be responsible for providing this infrastructure - the government, the private sector, or a combination of both?

Private firms can efficiently provide services where users can be charged, and competition is possible. However, they tend to undersupply essential services that users may be unable or unwilling to pay for despite their city-wide benefits, such as sanitation services. Certain goods, such as street lighting or pavements, are difficult for the private sector to provide because restricting those who can and cannot use them is difficult and unattractive. Government coordination, regulation, and in some cases provision of infrastructure and services will be crucial for inclusive urban and sustainable development.

Rising popularity of PPPs in low- and middle-income countries

Historically, public provision of infrastructure and services was either done directly by public employees or through procuring private companies to implement particular stages of construction or operation.

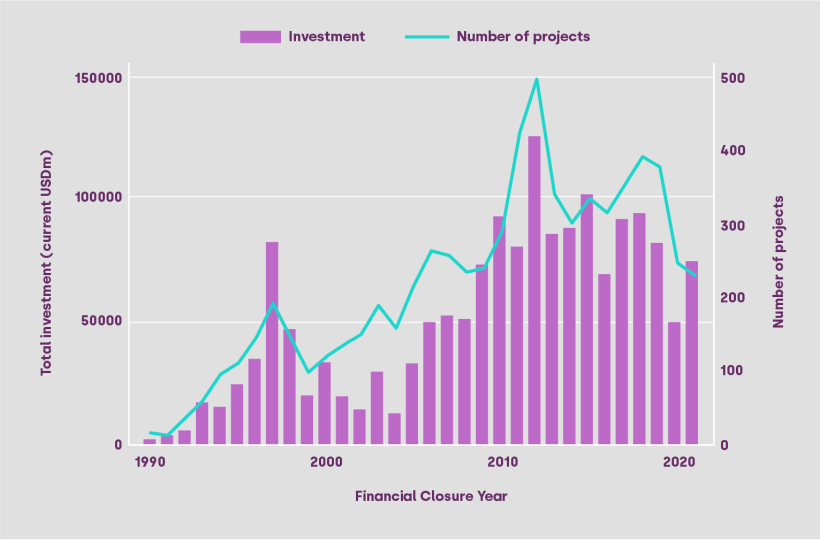

However, Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are becoming increasingly popular in low- and middle-income countries, especially since the late 1990s (see Figure 1 below). Through these, a private partner manages some or all aspects of the design, construction, operation, maintenance, and financing of infrastructure and services. These arrangements allow governments to share responsibility and risk with the private sector.

Figure 1: New PPP investments and projects agreed annually in low- and middle-income countries

Notes: PPPs have become especially popular since the late 1990s. Source: World Bank, Private Participation in Infrastructure Projects Database.

PPPs can have enormous advantages when designed well and for the right projects. As they bundle many aspects of design, construction, operation, and maintenance into single contracts, investments made at each stage are likely to account for costs at other stages as well, thus allowing for cost reductions and reduced delays across the life cycle of the PPP. They also allow governments to overcome short-term credit constraints by leveraging private investment for projects that generate new revenue streams through user fees. In the 1990s, faced with shortages in sewerage capacity, Durban successfully implemented a 20-year PPP aimed at recycling wastewater for industrial purposes that freed enough water to serve 400,000 people in the city.

PPPs cannot solve the government’s long-term fiscal problems

However, PPPs often run into problems when they are used to overcome government borrowing constraints. Crucially, PPPs do not reduce the financial burden of public infrastructure projects on governments in the long run, as these projects must eventually be paid for through government transfers or by foregoing revenues from user fees.

PPPs also have their own downsides - they can lead to prioritising cost minimisation over quality as the private party attempts to expand profit margins. Private efficiencies can also be counterbalanced by high private capital costs and the additional premium firms require to take on these projects.

Using PPPs also requires governments to be able to design and manage highly complex contracts. Contracts can be highly skewed towards private parties where this capacity doesn’t exist. In Latin America, 69% of all transport PPPs were renegotiated between 1988 and 2004 — mostly to benefit the private sector partner.

The right projects and conditions for PPPs

This trade-off requires careful consideration of where PPP contracts are better suited, as not all projects are suitable for PPPs. Evidence suggests PPPs work best:

1. Where private actors are incentivised to maintain quality and/or clear quality standards can be defined, measured, and enforced.

2. Where the service and infrastructure are extensive enough to justify the costs associated with designing and managing the complex contracts Typically, PPPs are best suited to projects that cost at least US$ 50 million.

Beyond selecting the right project for PPPs, governments need the right enabling conditions for success across all stages of the project life cycle. This requires strong regulations and institutions for managing PPPs, appropriate risk sharing between public and private parties, effective systems for monitoring private partner performance, and clear and reasonable terms for renegotiation. Many countries have built up dedicated PPP units or infrastructure delivery agencies that have such specialised capacity in managing these contracts.

PPPs are one of many procurement options

PPPs are an important and useful procurement option for governments to consider. But PPPs aren’t a silver bullet; they have clear trade-offs that must be carefully considered. If policymakers use PPPs to overcome short-term credit constraints, it won’t reduce the overall financial burden in the long run. If policymakers use PPPs to forgo building state capacity, the risk is that the government cannot effectively design and manage the contract, leading to significant financial costs for the treasury. Instead, PPPs should be used as a procurement tool: for the right project and with the appropriate enabling conditions.