Mobilising domestic revenue and tax incentives for economic development in Uganda

Tax incentives are a widely used tool by governments around the world to attract investment and promote economic growth. However, their effectiveness in Uganda has been called into question, with evidence indicating that they may be doing more harm than good and are not delivering on the promised benefits.

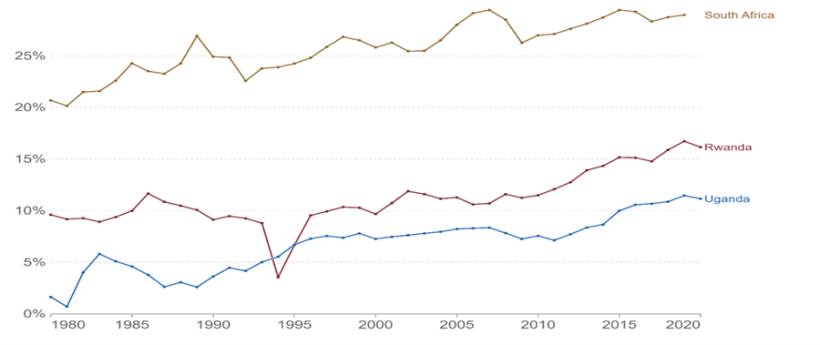

Governments around the world offer a variety of tax incentives to businesses, such as tax breaks, exemptions, and credits. These incentives are designed and expected to attract investment, create jobs, and stimulate economic growth and activity. Yet, Uganda's taxation landscape faces several challenges, the most pronounced being its enduringly low tax-to-GDP ratio. Although there has been an incremental rise over the years, it stands at 12%, which is markedly lower than many other nations -15% in Rwanda and nearly 28% in South Africa.

Figure 1: Total tax revenue, direct and indirect tax given as share of GDP 1980 to 2020

Note: The figure illustrates the total tax revenue, direct and indirect tax, given as a share of GDP from 1980 to 2020 for Uganda, South Africa, and Rwanda. While total tax revenue as a share of GDP has increased in all three countries over the past 40 years the rate of increase has been different in each country. Uganda's total tax revenue as a share of GDP increased from around 10% in 1980 to over 20% in 2020. While Rwanda's total tax revenue as a share of GDP increased from around 5% in 1980 to over 15% in 2020. Source: ICTD/UNU-WIDER Government revenue dataset, August 2021.

IGC Uganda in partnership with the Ministry of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development hosted the 7th Economic Growth Forum (EGF) in Kampala. Paul Lakuma (Senior Research fellow at the Economic Policy Research Centre) and Twivwe Siwale (Head of Tax for Growth at the International Growth Centre) discussed the pathway and challenges in raising tax revenue for economic development in Uganda.

Paul Lakuma explained that Uganda's tax incentive landscape represents high costs and low returns. Contrary to the general perception that tax incentives stimulate economic activity, his research showed that these incentives are mostly redundant and expensive, while the cumulative benefits remain marginal. He further argued that tax incentives in Uganda have failed to make significant impacts on exports, employment, or Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This is despite the fact that Uganda has a relatively generous tax incentive regime.

This unproductive tax system poses challenges to Uganda’s development, as revenue is essential for growth and development. Twivwe Siwale showed how that Uganda lags behind regional counterparts in tax-to-GDP ratio (see Figure 1). This notwithstanding, Uganda could raise more revenue by leveraging VAT, property tax, and corporate income tax, among other options.

Why is it difficult to raise tax revenue in Uganda?

The primary sources of revenue for Uganda are consumption tax, inclusive of VAT, and trade taxes. Twivwe Siwale explained that this reliance on certain forms of taxation reflects a focus on ease of collection rather than creating and instituting a diverse and efficient tax framework. Tax evasion further compounds the revenue collection challenges with enforcement proving to be a significant hurdle. Between 2013 and 2016, Uganda witnessed a loss of at least US$ 383 million in revenue due to VAT evasion alone.

Property tax, a substantial revenue source for high-income countries, is under-leveraged in Uganda. For instance, in the capital Kampala, a mere 12% of properties settled their tax dues punctually in the fiscal year 2019-20, collecting only 34% of the prospective revenue. Personal income tax (PIT) also presents a disconcerting trend. While wealthy countries see roughly 50% of their populations contributing to PIT, in Uganda, as in most sub-Saharan African countries, the figure is low. Despite the PIT system in Uganda being designed to be progressive, only 5% of company directors and an insignificantly small proportion of high-ranking government officials, many of whom possess extensive assets, pay personal income tax.

Moreover, tax exemptions and incentives, often championed as vehicles for attracting investments and spurring economic growth, have become a point of contention. Specifically, Uganda has forgone collecting up to 2% of its GDP due to the preferences given to a select group of taxpayers. Between 2014 and 2018, Uganda saw a staggering loss of UGX 2,411 billion (roughly US$ 424 million) due to corporate income tax (CIT) and customs tax exemptions.

Pressing need for policy change around tax incentives

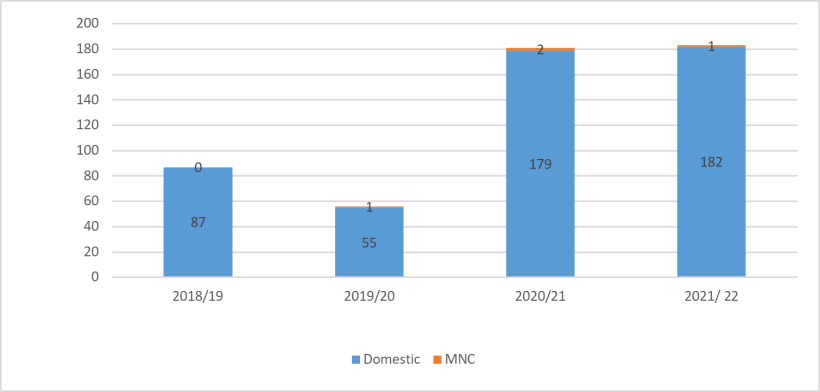

Uganda introduced 10-year tax exemptions as a key incentive, which Paul Lakuma argued have failed in attracting notable FDI. Uganda's tax legislation offers various exemptions intended to further investment and other economic goals. These are aimed at enhancing employment, increasing exports, and encouraging the use of domestic labour and raw materials. Strategic investors can benefit from exemptions on income tax, VAT, excise, and stamp duty, provided they meet specific qualifying criteria. Paul Lakuma’s research indicates that these incentives have been ineffective in attracting multinational corporations (MNCs) and have not led to notable increases in exports or employment.

Figure 2: Number of new qualifying firms (domestic and MNC) for 10-year tax exemption since 2018-19

Note: This figure illustrates the number of new qualified firms (domestic and MNCs) that have been granted a 10-year tax exemption since the 2018-19 fiscal year. It shows that the number of new qualified firms has increased each year, from 110 in the 2018-19 fiscal year to 200 in the 2022-23 fiscal year. While this is a positive trend, the graph also shows that the majority of new qualifying firms are domestic firms, indicating that while tax incentives have encouraged domestic investment, the same is not true for foreign direct investment (FDI). Source: Presented by Paul Lakuma at the 7th Economic Growth Forum in Kampala.

Furthermore, the deemed VAT scheme (a VAT relief mechanism where VAT payable on a taxable supply is charged but not paid by the recipient of the taxable supply) has become redundant, with numerous agencies that would typically contribute now taking advantage of this system. This misuse is further compounded by the poor administration of the incentives. Many firms that benefit from these schemes often neglect their obligations, failing to file for PAYE, exports, and investment. On the brighter side, the majority of incentives such as VAT zero rating, industrial parks, and free-zones, appear to be effectively targeting the manufacturing sector. These specific incentives address the unique needs and challenges of the manufacturing industry, ensuring that they can genuinely benefit from the support.

Policy options and key takeaways

Rethinking Uganda's tax incentives for tangible economic growth

A comprehensive overhaul of Uganda's taxation system is crucial for its economic growth. First and foremost, there is an immediate need to rationalise tax exemptions and incentives. Often referred to as the 'low-hanging fruit', streamlining these provisions represents the most straightforward and least expensive way to bolster revenues. There is a growing consensus on the need to abolish the 10-year tax holiday, as it hasn't yielded the desired results of attracting substantial investments. Instead, a more pragmatic approach would be to consider implementing a minimum lower tax rate, which might offer a more attractive proposition for potential investors. Furthermore, to ensure a balanced fiscal approach, presenters at the 7th EGF proposed the removal of certain incentives that might not be serving their intended purpose, for example the 10-year tax holiday.

The deemed VAT regime's scope should be narrowed, restricting its application solely to the extractive sector. This focused approach might ensure that the scheme is used more efficiently and in sectors that truly need it. Paul Lakuma’s research suggested considering co-financing donor projects could optimise resource allocation.

Unlocking revenue potential through property tax

Harnessing underutilised tools like property tax can significantly augment national revenues. This can be achieved through a multifaceted approach: implementing simple enforcement reminders can prompt timely tax payments; linking property rates to tangible benefits can heighten citizen engagement and compliance; improving rapport with KCCA officials and rectifying information discrepancies can streamline the taxation process. Investing heavily in property registration, leveraging emerging digital technologies, and broadening the tax base are also pivotal measures.

Tackling tax evasion across all categories is paramount for economic development

The needs an enhanced application of technology and diligent use of data, including third-party information. An exemplar in this realm is the targeted identification of High-Net-Worth-Individuals (HNWI), utilising the wealth of information available to the government. Focusing on VAT, Uganda can significantly benefit from the effective use of technology, much like the Electronic Fiscal Devices (EFDs) employed by Rwanda, resulting in a 5.4% surge in VAT revenue.

Enhancing tax administration is key for tax compliance

Streamlined processes and stringent monitoring can improve compliance, which requires entities to be diligent in their filings. Better administration and governance are essential for achieving this goal. The misuse of tax incentives in particular, signals a larger problem of poor administration and compliance, while Twivwe Siwali's presentation suggests that the future of Uganda's fiscal capacity lies in data-driven policy and robust administration.

Conclusion

Uganda stands at the precipice of an economic transformation, but for this transformation to be realised, the country needs to be prepared to challenge the status quo, especially in the realm of tax incentives. There is an urgent need to overhaul current provisions, such as the 10-year tax exemption. A more practical solution might be the introduction of a minimum lower tax rate coupled with a refined VAT regime and the possibility of co-financing donor projects.

Uganda’s untapped potential in property tax can serve as a key revenue catalyst. Effective strategies, from simple enforcement reminders to enhanced digital platforms and fostering relations with KCCA officials, can drive this forward. Similarly, addressing tax evasion through more sophisticated methods, including the targeting of HNWIs, is pivotal to improving tax administration which is central to Uganda's fiscal trajectory.

There is also a pressing need for a modernised taxation approach in Uganda. The consensus is clear: for a prosperous Uganda, a shift towards data-informed policy and robust administration is imperative. It's about shaping a future centred on efficiency and growth.