Zambia's pathways to growth

Research and data can play an important role in helping Zambia chart pathways to economic growth that reduce poverty and is inclusive through improving productivity of people and firms.

Zambia has struggled to reduce poverty and create a sustainable pathway to growth, in spite of periods of rapid economic growth, particularly during increased global demand for copper. Several structural issues constrain this ability, including low agricultural productivity, dependence on the copper sector, and high levels of regional inequality.

A year ago, the IGC established a new country office to scale up our decade-long partnership with Zambian policymakers by producing research and analysis on key government priorities. There is an urgency to support evidence-based reforms in Zambia. With ongoing debt restructuring and a predicted shortfall in meeting global copper demand, Zambia has an opportunity to unlock sustainable and inclusive pathways to growth, especially those that allow people to withstand the impacts of climate change better.

Pathway 1: Improve agricultural productivity that increases farmer incomes and export earnings

Agriculture is a fundamental pillar in Zambia’s economic and social fabric. It accounts for 3.4% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employs 59% of the workforce. However, the agricultural sector faces numerous challenges that hinder its productivity. These challenges include inefficient government policies, the impacts of climate change, market inefficiencies, limited access to credit, inadequate road infrastructure, and low adoption rates of modern agricultural technologies. As a result, much of the sector operates at merely 20% of its potential capacity.

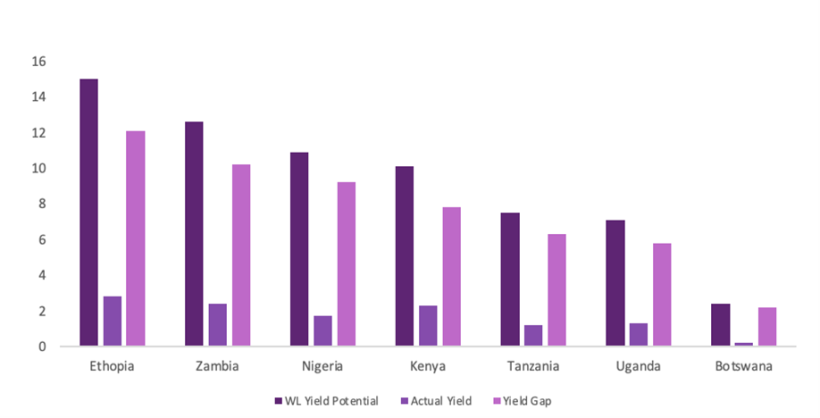

Illustrating this stark reality, Figure 1 depicts the significant disparity between potential and actual agricultural outputs. Under ideal conditions and utilising best practices, Zambian farmers can achieve maise yields as high as 12.6 tonnes per hectare. In contrast, the current average yield is approximately 2.4 tonnes per hectare. This vast difference of about 10 tonnes per hectare is among the highest in the region. Moreover, only 15% of Zambia's arable land is being cultivated.

This underutilisation highlights the enormous potential for Zambia to increase its agricultural production significantly. Such expansion could meet the increasing global and regional demands for key crops like soybeans and maize and substantially contribute to Zambia's economic development and food security.

Key actions can be taken today to unlock the country’s agricultural potential, including:

- Promoting competitive markets for essential inputs such as fertiliser and ensuring stable export markets are critical for enhancing farming profitability.

- Researching to assess and refine current agricultural policies would help optimise the efficiency of government programmes.

- Improving access to detailed weather forecasts would empower farmers to make better farming decisions.

Figure 1: Water-limited yield potential, actual yield, and yield gap for a selection of countries between 2000-2020

Notes: Zambia has one of the largest yield gaps in the region. Source: Global Yield Gap and Water Productivity Atlas.

Pathway 2: Expanding the mining sector's production and using it to build broader productive capacity

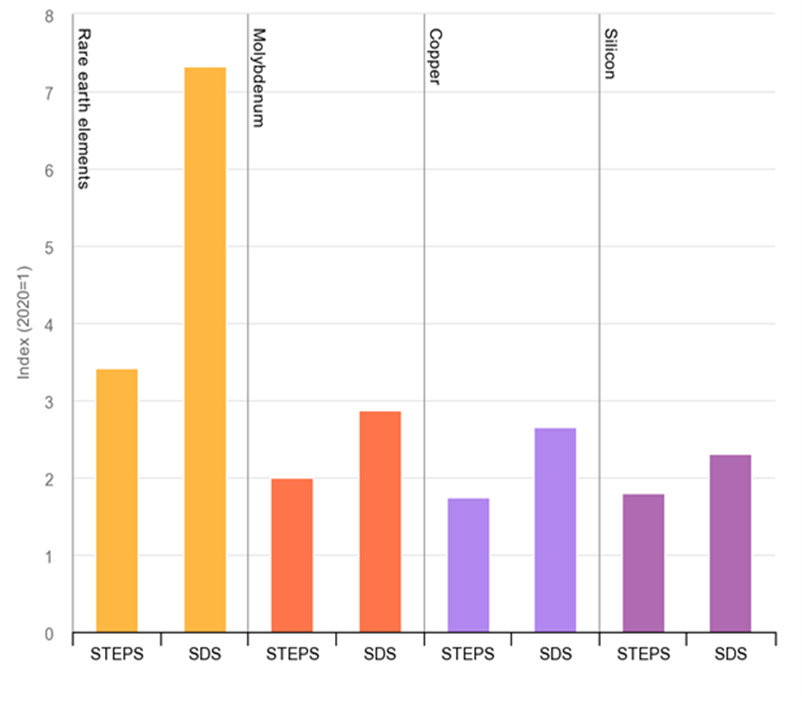

The global energy transition away from the use traditional fossil fuels to cleaner alternatives is likely to increase the demand for copper, as illustrated in Figure 2, with projections suggesting a three-fold rise by 2040. This presents a unique opportunity for Zambia, which is home to 6% of the world’s copper, to capitalise on this anticipated resource boom to build productive capacity in the wider economy.

Based on Eric Werker suggestions in a recent IGC policy brief, three key actions can involve:

- Complementing efforts to increase minerals production, a strategic approach is required that involves fostering transparent benefit-sharing between mining firms and Zambians. This encompasses local content promotion, increased jobs for Zambians, and investment in local communities. This should also be augmented by promoting value addition and expanding mining beyond copper to include other mineral resources.

- Adopting internationally recognised supply chain standards for responsible sourcing of minerals is crucial to strategically position Zambia for the energy transition. This would leverage Zambia's position as a major supplier of critical minerals to promote responsible sourcing globally, particularly in challenging competitor environments.

- Growing the mining sector in a way that fosters investment in infrastructure development to improve transportation, communication, and energy networks, that are critical for wider productive capacity of the economy. Through value addition, the sector should support the growth of manufacturing and other non-mining sectors to create new jobs and reduce dependence on mining.

Figure 2: Growth in demand for clean technology minerals by 2040 relative to 2020 levels in stated policy (STEPS) and sustainable development (SDS) scenarios

Notes: According to the World Energy Outlook Special Report, the demand for rare earth elements (REEs) is expected to triple in the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) and increase more than seven-times in the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) by 2040, with mineral demand dominated by graphite, copper, and nickel. Clean energy technologies have become significant consumers of critical minerals, surpassing consumer electronics since 2015. This shift is part of the broader trend where energy transitions are becoming a major driver for the total demand growth of certain minerals. Source: IEA.

Pathway 3: Use place-based economic policies to reduce inequality and generate new growth regions

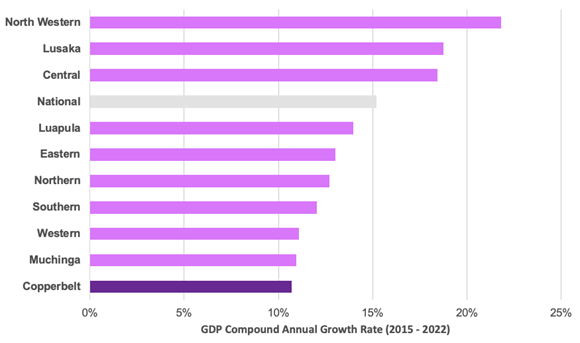

Zambia’s progress towards poverty reduction is hampered by growing inequality. Between 1996 and 2015, inequality in Zambia increased from 0.700 to 0.735, as measured by the Gini coefficient. One way to tackle this is to generate new spatial engines for growth by targeting investments in lagging areas. A candidate for this is the Copperbelt province in northern Zambia. It is the most urbanised province and second only to Lusaka in terms of contribution to national GDP. However, the province has faced considerable economic challenges recently. Figure 3 (from IGC’s upcoming policy paper) illustrates this concerning trend: the Copperbelt has recorded the lowest growth among all provinces since 2015. With a compound annual growth rate of 10.7%, it trails the national average by five percentage points.

Figure 3: Provincial GDP compound annual growth rates from 2015 to 2022

Notes: Sorted in descending order by growth rates. Source: ZamStats (2022) shared with the authors).

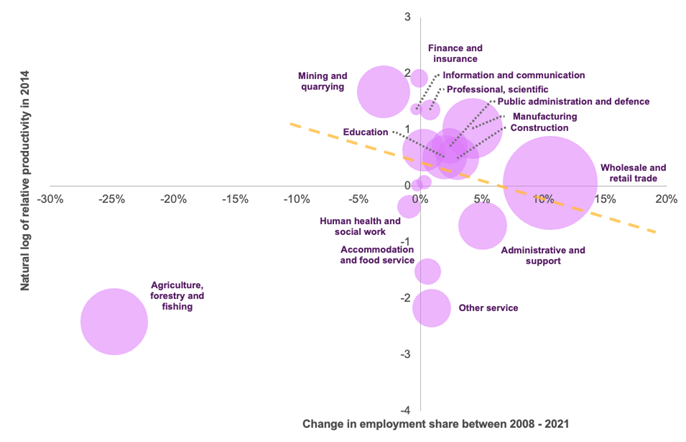

Several factors contribute to sluggish economic growth within the Copperbelt, including a lack of economic diversification, historically low copper production, and a structural shift towards industries with lower productivity. The broader national issue of limited economic diversification is particularly pronounced in the Copperbelt. At its peak, mining directly accounted for nearly 40% of provincial GDP, but this figure has now more than halved to just 18% based on data by the ZamStats. The downturn in mining output and revenues stems from various issues, including operational challenges, inconsistent tax policies, insufficient capital investment, and depressed copper prices. Moreover, since 2008, labour resources have been reallocated toward lower-productivity industries. The yellow trend line in Figure 4 illustrates this reallocation: excluding agriculture, which underwent a measurement change, labour resources appear to have shifted most towards lower productivity industries such as trade and administration services.

Figure 4: Shift towards lower productivity industries in the Copperbelt region of Zambia

Notes: Due to concerns regarding a change in the measurement of agriculture employment between pre- and post-2017 labour force surveys, the yellow dotted line is the linear trendline for all data, excluding agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Relative industry productivity is calculated for 2014 as this is the first year for both value-add and employment share by industry are available for the Copperbelt province. The bubble size represents the share of employment in 2021. Source: ZamStats (2022) shared with the authors.

Despite these challenges, the Copperbelt has significant untapped potential. The increasing global demand for copper has rejuvenated interest in the Copperbelt’s mines, with the two largest receiving substantial investment commitments. Beyond its traditional mining sector, the Copperbelt holds considerable promise in agriculture, manufacturing, regional trade, and the development of copper value chains. To capitalise on these opportunities and drive economic diversification, it is crucial to implement national-level and place-based policies that effectively address existing barriers, thereby paving the way for private sector-led growth in the province. An upcoming IGC policy paper will outline these options.

Pathway 4: Making public service delivery more responsive to people’s needs and informed by data

By expanding the Constituency Development Fund (CDF), a national fund that gives each of the country’s 156 constituencies with a budget to spend on local development, by 1700%, the government of Zambia is attempting to make the delivery of public infrastructure more responsive to local preferences. Decentralising service delivery also carries costs associated with lower capacity levels, corruption, and inefficient systems and processes. Data and experimentation can help find the appropriate level of authority to implement development projects: IGC’s learning programme on the CDF led by Katherine Casey has collected two rounds of primary data providing on-the-ground insight on the expanded CDF's constraints, giving policymakers insight in what is working and what isn’t, and is presently working on pilots that might alleviate these constraints.

As the CDF learning partnership shows, data is critical in making better policy decisions, especially when programmes have high budgets attached to them. However, there is a significant disconnect between data and policy decisions across the government. Zambia’s ambitions in the 8th National Development Plan recognise that this must change.

Doing so requires coordinated action on data's demand and supply side. The 2nd National Strategy for the Development of Statistics outlines the critical steps the government are taking to improve the data supply. These steps target the development of Zambia’s data infrastructure as they work towards centralising and integrating data while increasing its quality and accessibility. Notably, reducing accessibility constraints – via efficient data-sharing mechanisms – will strengthen Zambia’s resilience in times of crisis, making it easier to produce actionable data-driven policy analysis quickly.

On the data demand, there are opportunities to strengthen capacity and connect the data and policy lifecycles, an area of focus for the IGC:

- Developing partnerships between researchers and policymakers, which focus on co-producing data-driven policy analysis, will build sustainable technical capacity within the government.

- Using instruments such as forums and roundtables to disseminate examples of how data can inform policymaking will increase policymakers' innovative use of data.

- Connecting the data and policy lifecycles by having feedback loops and demand-led data collection will ensure data remains policy-relevant and policies are more impactful.

Deliberate policies, grounded in data and evidence, can help Zambia unlock pathways to growth that reduce poverty. There is an urgent need for this: 60% of Zambians still live in poverty, a higher incidence than in 2015. This is why, in 2024, IGC will publish several research and policy papers providing greater insights into these and other pathways to growth and working closely with the government partners in testing ways growth and prosperity can be generated and sustained.

The IGC has partnered with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Zambian Ministry of Finance and National Planning to co-host the 2nd Zambia Economic Growth Forum on 21 and 22 February 2024.